Queer Ecology and Urban Landscapes

What is Queer Ecology?

Queer Ecology is a conceptual framework to help shake off our preconceived ideas and projections of biases onto the natural world. Traditionally, ecology and the environmental movement have utilized rigid dualistic and binary approaches to define natural versus unnatural, wild versus domestic, inner and outer, and even what is living versus nonliving. Queer Ecology differs from other ecological perspectives in that it functions primarily as a verb — “queering” how we view and interact with nature and each other. First introduced by professor of Environmental Studies Cate Sandilands (Sandilands, 1994), queer ecology uses a practice called “queering” which means to look at life and each other with a fresh unbiased gaze. In her own words:

“A politics that would have us celebrate “strangeness” would place queer at the centre, rather than on the margins, of the discursive universe. It is not that we encounter “the stranger” only when we visit “wilderness,” but that s/he/it inhabits even the most everyday of our actions. To treat the world as “strange” is to open up the possibility of wonder, to speak also with the impenetrable spaces between

the words in our language.” (Note that the featured image above shows homosexual barn owls from the NWF Blog by Braelei Hardt, June 22, 2023.)

We think most simply of “Queer” as an adjective describing both gender identities and sexual identities that do not fit into cis/trans gender or hetero/homosexual binaries. Gender is a cultural construct and realistically is a spectrum with some falling neatly at the cis and trans ends and many others somewhere in between. With a queer ecology perspective, we can see that nature is very queer in the sense that monogamous sex partners are rare and sex is often used for purposes other than reproduction. See the references and readings below to delve deeper into this topic.

More broadly, nature is queer because there is a lot of interdependency and interactions across categories that we might view as limiting but actually aren’t.

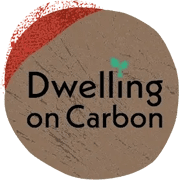

The lifecycle of the multicellular and microscopic rotifer, shown in the lefthand image above, is an example of what I am calling “sexual queerness”. A heteronormative perspective would have you look for sex for reproduction and sex that is heterosexual and monogamous. The rotifer alternates between asexual reproduction where the females produce clonal copies of themselves (parthenogenesis), and sexual reproduction where the sex determination is based on sets of chromosomes. One set of chromosomes (haploid) defines you as a male rotifer, suitable only for fertilization, while two sets (diploid) defines you as a female rotifer. I love the “strangeness” of these sexual habits!

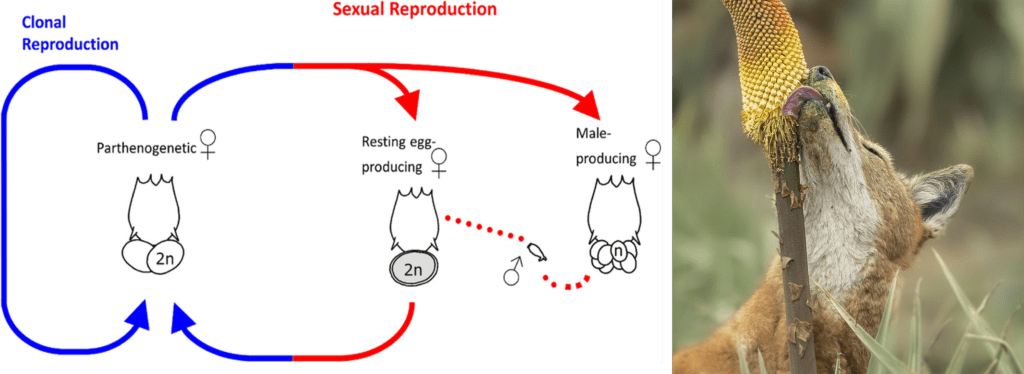

The behavior of the Ethiopian wolf, shown in the righthand image above, is to devour the nectar from the red hot poker flower. I consider this an example of “identity queerness”. With a dualistic perspective one would not expect wolves to pollinate these flowers and yet the same wolf can be seen visiting many flowers in one session — clearly transferring pollen. My point here, and of course there are countless more examples, is that nature is inherently “queer” — messy, transformative, and full of surprises that exhibit lots of interdependency. A queer perspective fosters innovative ways of seeing the world including questioning assumptions and the status quo. As someone who identifies as queer, I understand what it means to “not belong” and am therefore very sensitive to the “othering” of nature and also open to phenomenon that challenge the heteronormative viewpoint.

How does “Queering” differ from “Rewilding”?

The term “rewilding” is defined as letting nature take its course after minimal intervention — which often includes re-introducing a keystone species. In our polyculture lawns, that intervention is the application of a diverse seed mix in a layer of compost and the keystone species are native seeds that provide host and habitat for a wide range of pollinators (seeds for plants including Phacelia, Lupine, and Bird’s foot trefoil). A popular example of rewilding is the re-introduction of the gray wolf to Yellowstone National Park (see below), which has resulted in a big increase in biodiversity including the return of beaver populations. It is important to understand that when Yellowstone first became a National Park in 1872, the Indigenous People living in that area were forcibly removed. This is an example of “green colonization” which unfortunately continues to this day with policies such as 30 by 30. So as much as I love the feeling of the word “rewilding”, it is a term that I will use cautiously if at all from hence forward. Keep in mind that if we do “rewild”, we need to first “rewild” ourselves; “untame” may be a slightly better way to express this sentiment.

Credit: Great Falls Tribune, January, 2015

Queering Polyculture Lawns

Fundamentally, the implementation of polyculture lawns is a “queering” of urban landscapes because it represents and requires a major shift in how we relate to these landscapes. Rather than thinking of your lawn, garden, or yard as a status symbol that sets you apart from your neighbors and shows off your perceived station in life, a polyculture landscape becomes a relative that you interact with in a reciprocal way. When you plant a seed mix that is rich in diversity, the expression of those plants will evolve over time in the process of succession — which occurs throughout nature. Early in the process, you may see predominantly annuals which act like sparkplugs to bring carbon into the soil and wake up the soil microbiome in all of the seeds and existing soil. Over time, perennial grasses and flowers will begin to dominate the landscape. A polyculture landscape invites interaction — observing the many birds, butterflies, lizards and rabbits that may visit, and noticing the many scents and colors that occur. Knowing that your garden is helping to cool your neighborhood and sequester carbon can also help with climate grief and doom spiraling.

Closing thoughts

Queer ecology builds on the ecofeminism movement, which explored the relationship between women and nature and noted that patriarchal society exploits both. In breaking down binaries, Queer ecology expands the traditionally feminine nature of Earth to include both masculine and feminine capacities. The concept of “ecosexuality” denounces the idea of nature as mother and instead sees it as a lover because “to be someone’s lover is more open-ended than being their mother as the lover assumes a relationship based on romance, sexual attraction and sensual pleasure and the lover’s relationship does not assume identities that conform to the gender binary” (Sprinkle and Stevens, 2021).

We are in a time politically in which both our planet and people who identify as queer are in grave danger. Using a queer lens to imagine healthier urban ecosystems provides the big thinking of inclusive and intersectional relationships that is needed in this moment. Stay tuned for more on this topic!

Readings and References

Bagemihl, Bruce (1999) “Biological Exuberance”

Driscoll, E (2017) “Bisexuality can benefit animals”; ScientificAmerican.com

Roughgarden, J (2024) “Evolution’s Rainbow”

Sandilands, C (1994) “Lavender’s Green? Some Thoughts on Queer(y)ing Environmental Politics” (https://doi.org/10.25071/2292-4736/37697)

Sheoran, M (2024) “Audre Lorde and queer ecology: An ecological praxis of Black lesbian identity in Zami” (https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2024.2362115)

Sprinkle, A and Stephens, B (2021) “Ecosexuality: The story of our love with the earth”

cyberleninka.ru/article/n/ecosexuality-the-story-of-our-love-with-the-earth/pdf

Resources

The Queer Sol Collective

Jason Wise Queer Ecology Hikes (LA)

500 Queer Scientists